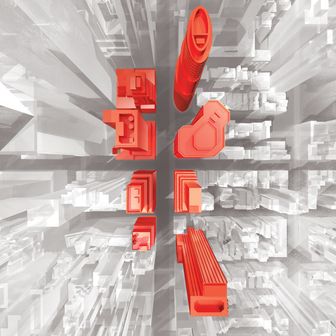

Not every unleased New York office building is alike. There are a few familiar types languishing on the market — the drab, dated high-rises in less than ideal neighborhoods and newly renovated glass towers arriving into an extremely oversaturated rentalscape. Then there are the buildings that become something else altogether; they stop being offices, and an enormous amount of financing and construction transforms them into (probably more profitable) residential buildings.

The Blah Glass Tower

850 Third Avenue

Built: 1960

Square feet: 617,000

The glass ziggurat at 850 Third Avenue is the architectural equivalent of The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit: sharp, straitlaced, and way past its prime. Its 21 stories were the height of corporate chic when the building first opened; this spring, the Chetrit Group sold the whole thing back to its lenders for $266 million, roughly $150 million less than it had paid only four years prior. After losing Discovery, Inc., during the pandemic, a major tenant that rented 160,000 square feet over seven floors, the building sits half-empty and brokers say it’s in dire need of a face-lift. The decline in the building’s fortunes stands in sad contrast to its once-vaunted tenant list, which included the offices of the International Herald Tribune and of Emery Roth & Sons, its architect.

The Shiny New One Without Tenants

111 Wall Street

Built: 1966

Square feet: 1.2 million

When Nightingale Properties and Wafra Capital Partners (now InterVest Capital Partners) bought a $195 million long-term leasehold on this nondescript office tower in 2020 with plans for a major upgrade, it was something of a bold move. Citigroup, which had used the entire building as a back office (operations, technology, administrative work), had vacated the year before. Other banks, too, were consolidating and moving their offices uptown. And 111 Wall had never been a truly top-tier building — when it opened, the First National City Bank leased most of it as storage for the batteries that ran its computers. But while a makeover wasn’t going to bring back the banks, plenty of tech and finance firms could, presumably, be interested in leasing space there. Then COVID hit. Almost three years in, 111 Wall — and its neighbor 60 Wall — is nearing the completion of costly renovations; 111 Wall, which cost $100 million to renovate, will have a bronze-trimmed glass façade, herringbone travertine floors, and 45,000 square feet of hospitality-style amenities for office workers. The two buildings combined will bring around 2.5 million square feet of gorgeous new office space to a business district with a 25.6 percent vacancy rate. 111 Wall hasn’t signed any leases yet, according to CoStar, though Nightingale says it’s in active negotiations with a number of tenants.

The Mid-Block Dump

29 West 35th Street

Built: 1911

Square feet: 85,000

There’s a certain kind of building that belongs to the side streets of midtown. Sand-colored or gray stone façade, dust-smeared windows, sooty bits of ornament — this is the sturdy, indefatigable mid-block dump, home to C-class office space that, while never exactly desirable, has always been abundant and convenient and reasonably cheap, providing respectable digs to generations of furriers and printshops and makers of children’s underwear. The downturn in the commercial market has been cruel to these properties — what with their relative lack of amenities and poor energy efficiency — and it’s been especially bad for 29 West 35th Street, a handsome if undistinguished 12-story office high-rise. At present, the building appears to be headed for auction after Paul Sohayegh and Roni Movahedian defaulted on their $41 million loan last year. Sadly, the building’s demise is no more remarkable than the building, yet for lovers of the area’s oddball urban fabric, it’s an ominous sign, boding ill for every seventh-floor leather-repair outpost and storefront sequin shop from Madison Square to Columbus Circle.

The Residential Conversion

160 Water Street

Built: 1972

Square feet: 525,000

This 24-story Financial District office building was once home to international banks and insurance companies, but by 2019, the glass tower was showing its age — one of many dated office buildings clustered around the South Street Seaport. A few years earlier, the owner, Vanbarton Group, had converted 180 Water, the tower’s neighbor, into a luxury rental. After the pandemic, the choice was obvious: office space no one wanted, or apartments in a desirable residential enclave with a new Whole Foods and Jean-Georges Vongerichten’s food hall? “There are many factors that go into determining office versus residential, but first and foremost, it’s location,” says Robert Fuller, principal and studio director at Gensler, the architecture firm that’s overseeing the building’s conversion into 588 market-rate studios and one-bedrooms (there’ll be a few two-bedrooms). In other ways, 160 Water wasn’t an ideal candidate for conversion: Modern office buildings often have deep floor plates with lightless interiors and glass curtain walls. But those things can be worked around. Gensler ran shafts through the center of the building and replaced drafty old glass curtain walls with high-end Skyline windows, which can be opened. The building will likely be rental rather than condo (condos require better bones). And almost half the units will have home offices.

More on the office apocalypse

- Tennis at the Former Hotel Pennsylvania, Anyone?

- Offices Are the New Malls

- The Teetering Tech Office