When Townes Coates, president of the Players, joined the organization in 2016, the furniture and artifacts in the Edwin Booth Room looked roughly the same as when Booth died over a hundred years prior: A bronze casting of Booth’s daughter Edwina’s hand in his on the living-room table; a portrait of his first wife, Mary Devlin, in the parlor; and, in a corner to the left of the fireplace, a locked cabinet.

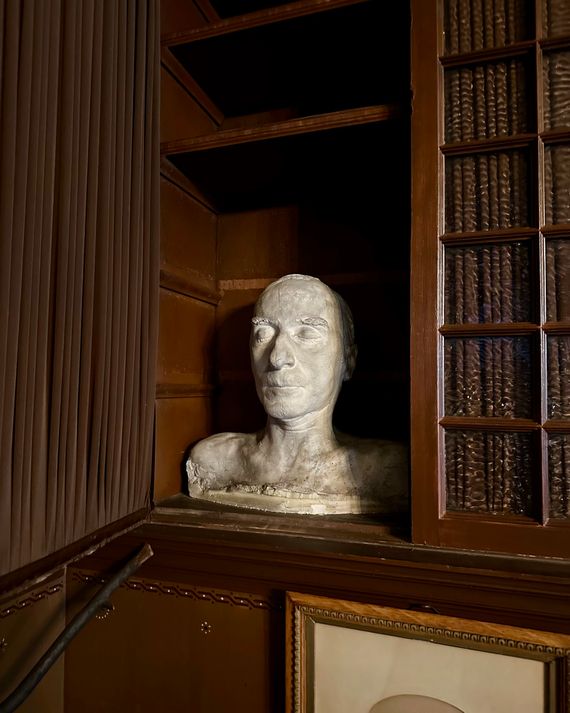

“It has been locked the entire time we have been here,” says Coates. “We always thought it was an air shaft between us and the National Arts Club.” But two years ago, the club and its adjoining nonprofit, the Players Foundation for Theatre Education, embarked on a massive restoration of the Booth Room, hoping to refurbish every inch of the space — which, this summer, meant finally opening the cabinet. The architects tried out a giant box of keys that had been in the office for “who knows how long,” says Tim Redmond, vice-president of the foundation. But alas, none worked. So, they took the door off its hinges. Inside, they found a death mask of Booth, cast in plaster. They later discovered, in the club’s archives, that the last mention of the mask had been in the 1950s, meaning it had been locked up for nearly a century. “And it was done the morning after his death in this room,” says Coates.

Booth, a renowned Shakespearean actor throughout his life, is probably better known today as the brother of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth. He created the Players Club in 1888 after purchasing the mansion at 16 Gramercy Park South, hoping to create a club where performers and artists of all stripes could gather and always have a room to stay in. When he bequeathed the mansion to the Club, he had just two requests: that the building remain a club in perpetuity, and that the architect Stanford White, who did the interior design, create a permanent room for him. Coates plans to keep the mask in the cabinet, only displaying it for special events or occasionally to Club members.

The painstaking first two phases of the restoration, led by conservation specialists at EverGreene Architectural Arts, included renovating the windows and shutters, long boarded up with plastic and shades to combat sun damage. Underneath layers of paint, they also uncovered the room’s original wallpaper and recreated it on both sides of the room. They’ve cleaned and reframed artwork and restored a number of furniture pieces, including the day bed, dressing table, leather wing chair, banister chairs, and chandelier. More work is still to come. Ultimately, says Redmond, “the goal is to see what Booth saw when he lived here.”

More Great Rooms

- Keeping It Simple on Lower Fifth

- Artist Vivian Reiss’s Murray Hill House of Whimsy

- Ryan Lawson Lives Above His Favorite Italian Restaurant